Introduction

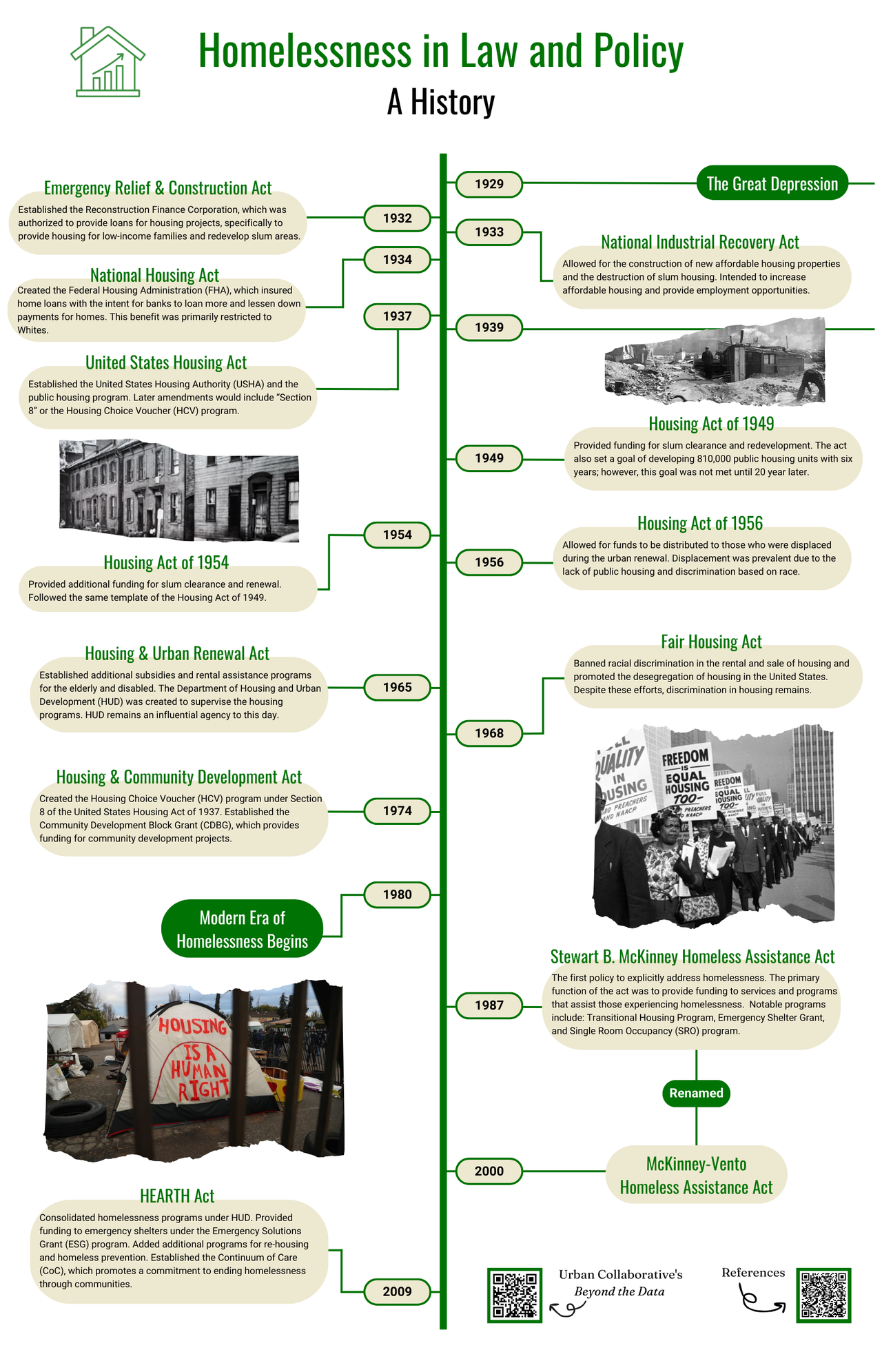

The history of homelessness and affordable housing in the United States is long and complex.

There are countless federal policies that attempt to establish and increase affordable housing for Americans; this fact makes it difficult to establish a comprehensive history of affordable housing policy in the United States. Additionally, federal policies that attempt to address homelessness are often disguised as housing policy and fail to directly mention homelessness.

This article seeks to provide a history of homelessness throughout the United States, highlight important federal policies related to homelessness and affordable housing, and dive into some state level policies targeting homelessness.

History of Homelessness in the United States

The history of homelessness in the United States dates back to the Civil War (1870s); however, modern homelessness is much different than the homelessness of that time. Post-Civil War homelessness primarily refers to individuals who chose to traverse the US looking for employment opportunities (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine [NASEM] et al., 2018). The perception of these individuals was negative, with them being referred to as “tramps” and seen as abandoning the long-held idea of homelife (NASEM et al., 2018). To address the increasing number of “tramps”, areas sought to increase employment opportunities to promote settling in one place (NASEM et al., 2018). At this time, policies addressing homelessness were left up to the individual states (NASEM et al., 2018); it was not until the emergence of the Great Depression that federal policies for affordable housing would be enacted.

The Great Depression lasted a decade, from 1929 to 1939, and was one of the largest economic collapses in modern history. Over ten million Americans lost their employment during this period (History.com editors, 2022). In turn, millions of Americans lost their housing as they could no longer afford rent or mortgage payments. As a result, many newly homeless Americans formed “Hoovervilles”, or encampments, where makeshift shelters were created (History.com editors, 2022). In some instances, these encampments were well run and had structure, such as a spokesperson or unofficial mayor, while others lacked any structure and became unsanitary (History.com editors, 2022). In response to the increasing number of individuals experiencing homelessness, President Herbert Hoover signed into law two acts, Emergency Relief and Constructs Act of 1932 and National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933, that sought to increase the availability of affordable housing (History.com editors, 2022). While the acts fail to mention homelessness explicitly, increasing the availability of affordable housing acts as a preventative measure by lowering housing costs with the hopes of nonpayment decreasing which results in fewer individuals becoming unhoused. Despite millions of Americans becoming homeless, the modern era of homelessness had yet to begin.

The late 1970s and early 1980s marked the beginning of what some call the modern era of homelessness (NASEM et al., 2018). Like Hoover’s Emergency Relief and Constructs Act of 1932 and National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933, many policies introduced in the 1970s that address homelessness did not explicitly mention homelessness and sought to increase access to affordable housing. The early 1980s was met with a significant spike in homelessness (NASEM et al., 2018). There are many factors that contributed to this spike, with recession and federal budget cuts being an influential factor (NASEM et al., 2018). In addition, deinstitutionalization, which was the process of closing state hospitals and asylums, was in full swing at this time (NASEM et al., 2018). Deinstitutionalization resulted in potentially millions of individuals with mental health issues and disabilities being put into their communities without any significant support; consequently, many individuals became homeless and stopped receiving treatment. This drastic rise in homelessness resulted in the first federal policy to explicitly mention homelessness, the Stewart B. McKinney Homeless Assistance Act in 1987.

The Stewart B. McKinney Homeless Assistance Act (1987), renamed the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act in 2000, continues to be one of the only federal policies that explicitly mentions homelessness. Since 1987, the act has undergone several changes including a name change and a reauthorization. Many of the changes occurred in 2009 after the passage of the HEARTH Act, which established the Continuum of Care (CoC), designed to promote the ending of homelessness and funding for housing, and regulations that are followed to date.

History of Federal Policies Impacting Homelessness

The history of policies addressing homelessness often revolve around indirect actions related to affordable housing. Failing to explicitly address homelessness in federal policy is primarily a result of the stigma around those experiencing homelessness. A long-held idea is that individuals experiencing homelessness are choosing to be unhoused, which relates to the idea that the government should not provide support to those individuals. Despite this belief, homelessness has many causes, many of which are systematic. Affordable housing helps individuals experiencing homelessness or on the cusp of homelessness by offering housing at a more affordable rate, making missed payments less likely; however, affordable housing is not an all-encompassing solution to end homelessness. Other support systems need to be established that specifically target homelessness to have an effective solution. This section looks at federal policies and decisions that impact homelessness, many of which are focused on housing affordability and development.

Emergency Relief and Construction Act of 1932 & National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933

Two significant policies were passed in the early 1930s to address the amount of affordable housing available to families. The first policy was the Emergency Relief and Construction Act of 1932, which established the Reconstruction Finance Corporation. The Reconstruction Finance Corporation was authorized to provide loans for housing projects, specifically to provide housing for low-income families and redevelop “slum” areas (NASEM et. al, 2018 & U.S. Congress, 1932). The National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 (NIRA) also sought to increase the availability of affordable housing. The act allowed for the construction of new affordable housing properties and the destruction of slum housing. These policies aimed to increase the availability of affordable housing options for low-income families. The availability of affordable housing can help prevent homelessness and may even allow individuals and families to exit homelessness. The acts had some success with increasing employment, but did not do enough to create lasting change (Corbett et al., 2014). While the Emergency Relief and Construction Act of 1932 had some short success, the NIRA was regarded as a failure. The Emergency Relief and Construction Act provided funds and work projects to help stimulate the economy, but the scope of those projects were not far reaching and were too late (Corbett et al. 2014). The NIRA was seen as a failure for several reasons, with the biggest being the amount of criticism received resulting in the act being short lived (National Archives, 2022).

National Housing Act of 1934

The significance of the National Housing Act of 1934 was the creation of the Federal Housing Administration (FHA). The FHA’s primary purpose was to make housing more affordable by insuring home loans and lowering down payments (Fritz, 2025). The FHA insured home loans for banks, which encouraged banks to approve more loans (Fritz, 2025). In addition, the downpayment price was decreased and loan lengths were increased (Fritz, 2025). Creating home loan programs expanded access to homeownership to those who had previously been excluded. Despite many individuals now being able to afford homes, people of color (POC) were excluded from taking advantage of loans (Fritz, 2025).

United States Housing Act of 1937 | Wagner-Steagall Act

The United States Housing Act of 1937, also known as the Nation Housing Act, Wagner Act, and Wagner-Steagall Act, was a progressive step towards housing reform. The act is primarily known for establishing the United States Housing Authority (USHA) and public housing. The initial success of the act is largely debated with some saying the act had too much input from conservatives (notable historians such as James T. Patterson and Rachel Bratt), while others find that the act was essential for the development of public housing as we know it today (historian Father Timothy L. McDonnell and analysts such as D. Bradford Hunt) (Hunt, 2005). The act provided funding for local housing authorities to build public housing units for low-income and working-class families.

Public housing is the oldest housing subsidy program in the United States (National Low Income Housing Coalition [NLIHC], 2019). Public housing is housing owned by HUD and operated by local Public Housing Authorities (PHA) (NLIHC, 2019). Low-income residents pay approximately 30% of their income in rent each month, which often includes basic utilities such as electricity and water. Today, the public housing program is expansive, with approximately 1.1 million units across the United States, in 2019, and 2.2 million residents housed (NLIHC, 2019).

The act would go on to establish the Housing Choice Voucher (HCV) program, also known as Section 8, by an amendment in the Housing and Community Development Act of 1974. Unlike Public Housing, the HCV program allows individuals to find rentals on the private market.

Housing Acts of 1949, 1954, & 1956

The Housing Act of 1949 was the first of several policies that intended to promote safe and affordable housing to all American families (NASEM, 2018; Von Hoffman, 2000). The act included a significant amount of money towards “slum” clearing for municipalities. It also included money for the development of affordable housing options; however, more housing was lost than what was gained (NASEM et al., 2018). As part of the policy, a goal was set to develop 810,000 public housing units within six years; however, this goal was not met until 20 years later (Von Hoffman, 2000). Municipalities were more likely to clear the slums, but not invest in new affordable housing development. When clearing the slums, displaced individuals were moved to public housing. Slums were areas that were considered blighted, or deteriorating, unsafe, overcrowded housing. Areas considered slums were often urban areas and populated by people of color (POC) and individuals in poverty. While the terms slum and blighted can refer to housing that is hazardous, redlining also played a role in determining areas as slums. Redlining is the process of determining areas where housing was of low-quality or hazardous; however, oftentimes areas would be determined “hazardous” for simply having POC residents. During this time, white flight, segregation, and redlining were impacting housing opportunities for POC. While the Housing Act of 1949 provided funding for the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), created under the National Housing Act of 1934, which distributed housing loans for families to move to the suburbs, it was restricted to Whites only. This created a concentration of poverty in urban areas with little quality housing options. (NASEM et. al, 2018)

The Housing Act of 1954 provided additional funding for urban renewal and slum clearance. This compounded the negative effects of the Housing Act of 1949 by further derailing the goal of public housing units built. The Housing Act of 1956 allowed for funds to be distributed to those who were displaced during the urban renewal (NASEM et. al, 2018). However, due to the lack of the public housing units available and interest in developing new housing by private developers, displacement was prevalent (Von Hoffman, 2000). In addition, these policies did little to stop discrimination and segregation of POC in public housing (Von Hoffman, 2000). The impacts and implementations of these policies spread to the 1960s, where the racial undertones of the policies became a source of criticism (Von Hoffman, 2000). While some cities saw small success from Urban Renewal, the results were regarded as poor due to standstills and slowed growth (Von Hoffman, 2000).

Housing and Urban Renewal Act of 1965

The Housing and Urban Renewal Act of 1965 provided similar funding to the previous housing acts; however, the Housing and Urban Renewal Act of 1965 established additional subsidies and rent assistance programs for low-income, disabled, and elderly households. Around the same time the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) was established to supervise the housing programs. (LBJ Presidential Library, n.d.)

The creation of HUD brought together five existing federal agencies: (1) The Federal Housing Administration, (2) The Public Housing Administration, (3) The Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae), (4) The Urban Renewal Administration, and (5) The Community Facilities Administration (HUD, n.d.a). All of these agencies played a major part in the federal government’s interventions for affordable housing. Today HUD remains an influential player in the United States housing game. HUD does a number of things with the primary responsibility being “national policy and programs to address America’s housing needs, that improve and develop the Nation’s communities, and enforce fair housing laws” (HUD, n.d.b). Some of HUD’s major programs include mortgage and loan insurance, Community Development Block Grants (CDBG), rental assistance (Housing Choice Vouchers [HCV]), public housing, homeless assistance, and fair housing enforcement (HUD, n.d.b). HUD is a primary funder for many local housing assistance programs and for certain outreach services through grants.

Fair Housing Act (1968)

The Fair Housing Act was a part of the civil rights movement to eliminate racial discrimination in most aspects of life including housing. The Fair Housing Act banned racial discrimination in the rental and sale of housing and promoted the desegregation of housing in the United States. In essence, the act made it illegal for individuals to be discriminated against based on race, religion, and national origin, with sex and disability being included later, by landlords, sellers, and financial institutions. HUD is responsible for the enforcement of the act and relies on reports from individuals to the Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity (FHEO). The result of breaking the Fair Housing Act includes fines after being determined and proven through a hearing before a HUD judge.

Despite the efforts of the Fair Housing Act, racial segregation remained prominent in cities and areas of concentrated poverty (Massey, 2015). According to Massey (2015), one of the major reasons the act sees a lack of impact is due to the burden of filing on the victim. The victim is responsible for filing a complaint and suing in civil suit for damages within 180 days (Massey, 2015). In addition to a time restriction on filing a civil suit, HUD has only 30 days to determine whether to proceed with the case or dismiss (Massey, 2015). Removing the burden and strict time frame from the victim may allow for the policy to be upheld to a higher degree.

Housing and Community Development Act of 1974

The most significant impact of the Housing and Community Development Act was the creation of the Housing Choice Voucher (HCV) program, commonly known as “Section 8” under the United States Housing Act of 1937. The HCV program provided rental subsidies to low-income families to rent in the private housing market. Participants are expected to pay a portion of their income (30% to 40%) while government funding covers the rest. The program is HUD funded and vouchers are distributed by local PHAs. Today, the HCV program is the largest housing program in the United States with more than 2.3 million households, or over 5 million individuals, enrolled in 2023 (McCarty, 2023). Despite being the largest housing subsidy program in the United States, waitlists for HCV are extremely high in some areas with local wait-times of over five years. In addition, discrimination and stigma of voucher recipients remains rampant, which results in a lack of housing options for voucher recipients. Conversely, allowing low-income families to rent on the private market allows them more freedom and choice on what type of housing they rent.

The act also established the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG), which included multiple urban development programs (NASEM et. al, 2018). The CDBG remains a primary funding source for community development projects today. Funds from the CDBG can be used for multiple projects that intend to improve the community, such as development of housing, community centers, restoration of housing, and more (HUD Exchange, n.d.).

Stewart B. McKinney Homeless Assistance Act (1987) & HEARTH Act (2009)

The Stewart B. McKinney Homeless Assistance Act was the first legislation that directly addressed homelessness in the United States. The 1987 act included twenty programs for emergency support of individuals experiencing homelessness. Some of the key programs include: the Emergency Food and Shelter program, the Emergency Shelter Grant, the Transitional Housing Program, the Supplemental Assistance program, and the Single Room Occupancy (SRO) program. These programs were designed to increase short- and long- term access to housing for unhoused individuals. The act allowed for funds to be given to different government agencies and nonprofit organizations to increase the availability of emergency shelter services. In addition to providing funding to housing programs, the act provided funding to several other programs to benefit the homeless population. Other programs include health services, food, education, and job training. The act also included specific funding for veterans experiencing homelessness. (Akins, 1988)

The act was renamed in 2000 to the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act. Despite the change in name, there were no significant changes until 2009 with the passage of the HEARTH Act. The HEARTH Act intended to consolidate homelessness programs, including the programs established by the McKinney-Vento Act, under HUD. The HEARTH Act provided funding to emergency shelters under the Emergency Solutions Grant (ESG) program. The act added additional programs for re-housing and homeless prevention. Prevention measures include rent and utility support, housing search assistance, and other effective measures. The HEARTH Act also established the Continuum of Care (CoC), which promotes a commitment to ending homelessness throughout the community. (Berg, 2015)

The HEARTH Act had some paramount impacts on how homelessness is addressed. First, the act shifted focus from emergency shelter to permanent housing and housing first principles (Leopold, 2019). The act did this by providing funds for rapid re-housing and establishing the idea that permanent housing should not be constrained based on individual factors like substance abuse or employment (Leopold, 2019). The impacts can be seen by the number of permanent housing beds surpassing the number of shelter beds in 2016 (Leopold, 2019). The act also established a “coordinated entry,” which created a standard process for connecting individuals to services based on their needs rather than each person applying to services individually or requiring a referral from an existing service or agency (Leopold, 2019). In addition, the establishment of the CoC was vital for understanding what policies are working and areas that need improvement (Leopold, 2019).

City of Grants Pass v. Johnson (2024) & Anti-camping Ordinances

The recent Supreme Court opinion, City of Grants Pass v. Johnson, has significant impacts on those experiencing homelessness. The case was concerning the legality of anti-camping ordinances in municipalities that do not have enough shelter beds for the number of individuals experiencing homelessness. A prior ruling in a Ninth Circuit Court established that anti-camping ordinances were unconstitutional under the Eighth Amendment which prohibits cruel and unusual punishment. The Ninth Circuit Court argued that it would be a cruel punishment for individuals experiencing homelessness to be punished for sleeping outdoors in public when there are not enough shelter beds available. The court argued that this would unfairly target homeless individuals.. The Supreme Court did not agree with the argument presented in the Ninth Circuit Court and ruled that anti-camping ordinances do not violate the Eighth Amendment. The Supreme Court opinion made punishing individuals for sleeping outdoors in public, even if they do not have anywhere to go, legal.

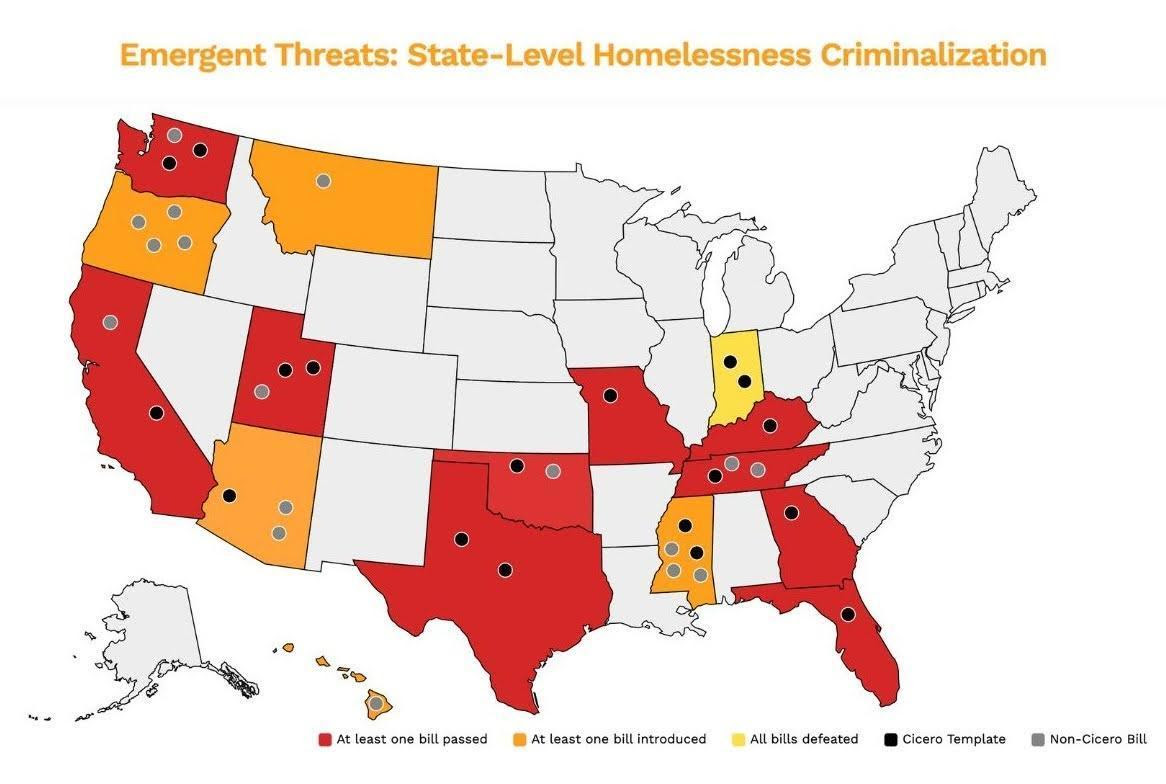

Since the Supreme Court’s opinion in City of Grants Pass v. Johnson, many municipalities have attempted to pass anti-camping ordinances. These ordinances directly impact the homeless population, making them more likely to go to jail and remain homeless due to cycles of recidivism that are well established in literature (Jacobs & Gottlieb, 2020). Approximately ten states have passed at least one bill related to criminalizing homelessness through anti-camping ordinances (Housing not Handcuffs, 2024).

Source: Housing Not Handcuffs (2024)

Pennsylvania

Act 1 of 2022

Act 1 of 2022 focuses on homeless youth who are school aged. Act 1 removes graduation barriers experienced by students experiencing homelessness, housing instability, or involved in foster care. The law does several things for students with housing insecurity including having a point-in-contact to be advised on their rights under the law, ensures equal access to extracurricular activities, fee assistance, and graduation support. Fee assistance aids in removing barriers from students enrolling in school sponsored activities and allows the opportunity to walk during graduation by covering regalia costs. The law also calls for timely graduations, which can be achieved by adapting flexible policies for graduation credits and establishing a plan with the student to keep them on track. Additionally, Act 1 allows for alternative pathways to graduation by allowing students to receive a diploma from a former school or the Pennsylvania Department of Education. Ensuring that young people are able to receive a degree is essential for them to access better employment opportunities. (Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, n.d.)

Housing Action Plan (2024)

In September 2024, Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro signed Executive Order 2024-03 – Housing Action Plan and Addressing Homelessness. In this executive order, Shapiro outlined five goals of the Housing Action Plan that include assessing and determining housing needs, the analysis of current resources, and recommendations of future action to address the needs. The plan is to be data-driven to achieve the best outcomes across the commonwealth. The Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Development (DCED) is tasked with taking the primary lead on the project in collaboration with other agencies. The executive order also details that a Housing Action Plan Working Group will be established to help the DCED complete its goals in data collection, analysis, and recommendations. The Housing Action Plan is to be presented to Governor Shapiro by September 2025. (Shapiro, 2024)

Other Policies

Housing First – Utah

Utah was one of the first states to establish a program based on the Housing First model, which prioritizes stable housing before any other intervention (PD&R Edge, 2022). Housing First allows individuals experiencing homelessness to receive housing before addressing less critical issues like behavioral health issues, employment, or substance use (National Alliance to End Homelessness, 2022). After securing housing, individuals are offered additional support services to help with things like employment, mental health, and a variety of other individual issues (National Alliance to End Homelessness, 2022). Utah began using the Housing First strategy in 2005 as an attempt to decrease chronic homelessness (PD&R Edge, 2022). Chronic homelessness in Utah decreased by 90% from 2005 to 2015; however, homelessness had a steep increase in 2022 with the number of individuals experiencing unsheltered homelessness doubling from 2018 to 2022 (PD&R Edge, 2022). This increase can be explained by the COVID-19 pandemic and skyrocketing housing costs. Despite the impressive reported reduction in chronic homelessness, some – mostly right leaning thinkers – believe that Housing First is not as successful. For example, Corinth (2016), a fellow for a center-right policy think tank, American Enterprise Institute, argues that the decrease in chronic homelessness in Utah is inaccurately reported due to changes in definitions of chronic homelessness and changes in counting methods. Research has found that Housing First and rapid re-housing has been helpful for connecting individuals to services and the individuals may be more likely to practice self care like taking medicine or receiving mental health treatment (García & Kim, 2020).

Homeless Bill of Rights (HBOR)

A Homeless Bill of Rights (HBOR) establishes basic protections for individuals experiencing homelessness. Rhode Island was the first state to establish a HBOR in 2012; Connecticut and Illinois have also established their own HBOR (Sequeira, 2024). A common component in a HBOR is the right to move freely, which protects the rights of individuals experiencing homelessness to be in public spaces (Sequeira, 2024). Additionally, the HBOR protects individuals experiencing homelessness from being discriminated against in employment, housing, and treatment (Sequeira, 2024). Despite the potential positive impacts of a HBOR, many advocates find that the law is not upheld (Sequeira, 2024). The HBOR has similar enforcement issues to the Fair Housing Act of 1968, where the burden is put on the individual being discriminated against. When the HBOR is violated, the individual may pursue a civil suit; however, individuals in poverty or experiencing homelessness may struggle to find resources to pursue a lawsuit. According to Robins (2022), it is too early to tell if a HBOR has the intended effects of treating individuals experiencing homelessness with dignity and respect.

California – Executive Order N-1-24

After the Supreme Court decision on Grants Pass, OR v. Johnson in 2024, California Governor Gavin Newsom signed Executive Order N-1-24. This executive order encouraged local municipalities to adopt similar measures when clearing homeless encampments. The clearing of encampments can be devastating for those experiencing homelessness. In many cases, individuals experiencing homelessness will lose most – if not all – of their belongings including important documents like social security card, birth certificate, and other forms of identification (Gutierrez III, 2023). In addition to promoting the clearing of homeless encampments, local governments were encouraged to use funding traditionally used for housing and intervention programs. The executive order includes that local service providers should be contacted for outreach services to those in the affected encampment; however, there is no guarantee that the individuals affected will be provided shelter or services. (Newsom, 2024)

Conclusion

The future of homelessness and homelessness policy is uncertain, especially given the change in administration and the rising cost of living. Homelessness is not an issue that will go away on its own or with simple intervention or policy. Homelessness is a very complex issue that impacts millions of individuals across the United States, therefore, a complex solution is required to solve the issue. Criminalizing homelessness, which has become increasingly popular among several states, is not an effective solution. In fact, criminalization can make homelessness much worse. Instead, policies and interventions should focus on preventative measures in addition to positive reactive measures, such as rapid re-housing. A two sided approach that supports those already experiencing homelessness through reactive policies and enacts preventative stopgaps is essential to ending homelessness. The government should not continue to avoid the word “homelessness.” Policies need to directly address homelessness rather than be disguised through affordable housing.

Kristie Houck is the Urban Collaborative Scholar-in-Residence at York College of Pennsylvania (YCP). During her time at YCP, Kristie has focused on housing research in York City. She is expected to graduate in May 2025 with a Masters of Public Policy and Administration (MPPA). Previously, Kristie’s professional experience was working with at-risk youth and their families involved in Children and Youth Services. Kristie can be found on Linkedin.

References

Akins, J. (1988). Necessary Relief: The Stewart B. McKinney Homeless Assistance Act. National Coalition for the Homeless. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=

Berg, S. (2015). Homeless assistance: McKinney-Vento homeless assistance programs. National Low Income Housing Coalition. https://www.nlihc.org/sites/

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. (n.d.). Act 1 of 2022: Supporting graduation for students experiencing educational instability. https://www.pa.gov/agencies/

Corbett, S.P., Janssen, V., Lund, J.M., Pfannestiel, T., Vickery, P., Wasiewicz. (2014). U.S. History: Reconstruction to the Present. https://guides.hostos.cuny.

Corinth, K. (2016). Think Utah Solved Homelessness? Think Again. Huffpost. https://www.huffpost.com/

Fritz, M.J. (2025). Federal Housing Administration. Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/

García, I., & Kim, K. (2020). “I Felt Safe”: The role of the rapid rehousing program in supporting the security of families experiencing homelessness in Salt Lake County, Utah. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(13), 4840. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-

Gutierrez III, N. (2023). “I’m Mostly Trying to Keep My Friends Alive”: Community Resistance to Homeless Encampment Sweeps in Los Angeles, CA (Master’s thesis, San Diego State University). https://www.researchgate.net/

History.com Editors. (2022). Hoovervilles. History. https://www.history.com/

Housing not Handcuffs. (2024). Emergent Threats: State Level Homelessness Criminalization. https://housingnothandcuffs.

HUD (n.d.a). A Brief History of HUD. https://archives.hud.gov/

HUD (n.d.b). Questions and Answers about HUD. https://www.hud.gov/about/

HUD Exchange. (n.d.). Community Development Block Grant Program. https://www.hudexchange.info/

Hunt, D. B. (2005). Was the 1937 US Housing Act a pyrrhic victory?. Journal of Planning History, 4(3), 195-221. https://doi.org/10.1177/

Jacobs, L. A., & Gottlieb, A. (2020). The effect of housing circumstances on recidivism: Evidence from a sample of people on probation in San Francisco. Criminal justice and behavior, 47(9), 1097-1115. https://doi.org/10.1177/

LBJ Library. (n.d.). Housing and Urban Development. https://www.lbjlibrary.org/

Leopold, J. (2019). Five ways the HEARTH Act changed homelessness assistance. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/urban-

Massey, D. S. (2015, June). The legacy of the 1968 fair housing act. In Sociological Forum (Vol. 30, pp. 571-588). https://doi.org/10.1111/socf.

McCarty, M. (2023). The Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher Program. Congressional Research Service. https://crsreports.congress.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Policy and Global Affairs; Science and Technology for Sustainability Program; Committee on an Evaluation of Permanent Supportive Housing Programs for Homeless Individuals. Permanent Supportive Housing: Evaluating the Evidence for Improving Health Outcomes Among People Experiencing Chronic Homelessness. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2018 Jul 11. Appendix B, The History of Homelessness in the United States. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

National Alliance to End Homelessness. (2022). Housing First. https://endhomelessness.org/

National Archives. (2022). National Industrial Recovery Act (1933). https://www.archives.gov/

National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty. (2018). From wrongs to rights: The case for Homeless Bill of Rights legislation. https://homelesslaw.org/wp-

National Low Income Housing Coalition. (2019). Public Housing History. https://nlihc.org/resource/

Newsom, G. (2024). Executive Order N-1-24. California. https://mclist.us7.list-

Office of Policy Development and Research. (2022). Salt Lake City Housing Authority services residents experiencing homelessness. https://www.huduser.gov/

Robins, K. (2022). What is a Homeless Bill of Rights, and which states have them?. InvisiblePEOPLE. https://invisiblepeople.tv/

Sequeira, R. (2024). As homeless people become more visible, some cities and states take a tougher line. Michigan Advance. https://michiganadvance.com/

Shapiro, J. (2024). Executive Order 2024-03: Housing Action Plan and Addressing Homelessness. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. https://www.pa.gov/content/

U.S. Congress. (1932). Reconstruction Finance Corporation Act: As Amended and Provisions of the Emergency Relief and Construction Act of 1932 Pertaining to Reconstruction Finance Corporation. https://elischolar.library.

Von Hoffman, A. (2000). A study in contradictions: The origins and legacy of the Housing Act of 1949. Housing policy debate, 11(2), 299-326. https://doi.org/10.1080/