Background: Grants Pass V. Johnson

A recent Supreme Court ruling threatens the unhoused and unsheltered populations throughout the United States. On April 22 the argument between City of Grants Pass, Oregon and Johnson was heard by the Supreme Court. On June 28, the Court released their opinion, which sided with Grants Pass. The argument was about the legality of public-camping ordinances, which prohibit the unsheltered population from sleeping outside in public spaces. Ordinances such as these had previously been ruled as unconstitutional. The Supreme Court has overturned the Ninth Circuit ruling, finding that public-camping ordinances are legal and do not violate the constitution under the Eighth Amendment (cruel and unusual punishment).3

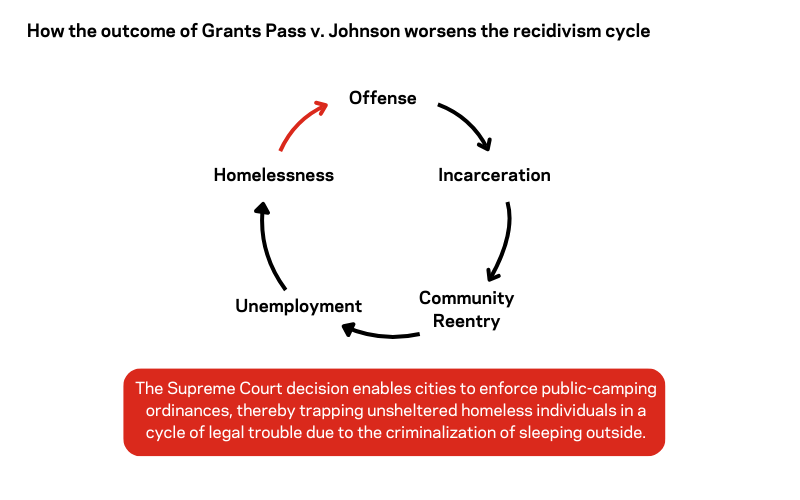

The Supreme Court ruling opens the door for cities to criminalize being unhoused, even where there are no shelter beds available, further entrenching the cycle of homelessness.

The Ninth Circuit’s Johnson v. City of Grants Pass 2022 ruling set the precedent that enforcing public-camping ordinances in locations that have a higher number of unhoused individuals than shelter beds is unconstitutional under the Eighth Amendment. In contrast, this 2024 Supreme Court ruling opens the door for cities and municipalities to create and enforce ordinances that criminalize being unhoused, even in cases where there are no beds available in shelters. Ordinances like the one in Grants Pass classify those sleeping outside as “campers” in public spaces rather than unhoused or homeless. Indeed, those without housing often have no choice but to violate public-camping ordinances like those passed in Grants Pass. Who comes to mind when thinking of individuals sleeping outside, in parks, cars, or benches? Likely, the unhoused. Although the court claims that this ruling is not a target on the unhoused, it will disproportionately affect them. Indeed, there is no stipulation that prevents cities or counties from using public-camping ordinances to target the unhoused population.3

Cyclical Recidivism

One concern that rises from this decision is its impact on the recidivism cycle. The recidivism cycle refers to the cyclical nature of crime, incarceration, and release.2 For example, Jacobs and Gottlieb found that “lack of regular housing at probation start and homelessness during probation interacted with criminal risk to predict recidivism… [I]n a context low in affordable housing and high in homelessness, moving to any residence may improve one’s circumstances and reduce recidivism.”7 The study concludes by encouraging “policies that ensure stable housing to probationers, including those otherwise classified as “low risk,” and research that understands the context-specific nature of residential circumstances.”7 However, anti-camping ordinances such as those in Grants do nothing to “ensure stable housing to probationers.” Rather, they criminalize the unhoused individuals experiencing homelessness by ensnaring them in this vicious cycle. Their crime: sleeping outside.

As it stands, individuals facing homelessness have a harder time obtaining employment. For example, navigating the job market without a permanent address, accessing hygiene, obtaining transportation, and acquiring other necessities needed for an interview make securing employment all the more complicated. If an individual is unhoused, they typically are also facing extreme poverty, which does not allow them to afford many belongings or basic necessities. If the unhoused population begins to be fined, or arrested, for sleeping in public, it will exacerbate their existing financial struggles and make it even more difficult for them to find a job. Similarly, the employed unhoused population will likely lose their employment if arrested, pushing them deeper into the cycle. Likewise, arrests will amplify their difficulties obtaining permanent housing.

Housing Wage

It is a misconception that all individuals facing homelessness just need employment to become housed. Many unhoused individuals have employment, but simply cannot afford market rent rates at their salary level.

According to the York County Economic Alliance, the County’s fastest growing industries are “transportation and warehousing (5,071 jobs); professional, scientific, and technical services (1,896 jobs); and agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting (348 jobs)”. Of these jobs of the future, only “…transportation and warehousing ($59,039) and professional, scientific, and technical services ($85,855) provided a living wage for employees.”12 Their report emphasizes that there are several industries in York where the average wages are below what is considered a living wage.12

According to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, the minimum wage to afford a two-bedroom apartment in York County without being cost burdened, (which means paying no more than 30% of income on rent costs) is $23.02.8 The average wage for renters in York County? $16.77—which totals in at less than $35,000 per year.8 Therefore, even the average employed individual in York could easily become unhoused due to unaffordable housing costs.

Support Services

The Supreme Court opinion discusses that shelters and supports will be offered before punitive action (in most scenarios); however, there are often not enough beds or spots available in local communities because of a dearth of funding. While support programs exist in most cities, including York, programs offered are not always ideal for everyone’s needs. Robin Shearer, the Executive Director of Friends and Neighbors of Pennsylvania, discussed some of the reasons why individuals experiencing homelessness may be hesitant to receive services or may reject the services altogether. One primary reason is a lack of trust due to prior trauma. Trauma can create hesitancy or refusal to accept a bed in a shelter due to the perceived lack of safety and privacy. Despite the hardships of living outside, many unsheltered individuals may feel safer because they have a community they trust.1

Another challenge that Shearer presented is the lack of accommodations for those with physical disabilities. It may be difficult for unhoused individuals who have disabilities to get into the shelter if there are stairs or if there are only top bunks available. Mental illness and substance use disorders can also contribute to an individual not being able to spend time in a shelter. Additionally, Shearer mentioned that the lack of freedom and choices can play a role as well: when going to a shelter, individuals may have to sacrifice what belongings and autonomy they do have to meet the requirements for space or shelter policies. This could mean sleeping separately from family members, forfeiting possessions that do not fit into the small allotment for each individual, or separating from a cherished pet. It’s not the case that people don’t want to sleep in a shelter. Rather, a complex array of individual circumstances might prevent them from doing so.1

Local Impact

In York County, there are public-camping ordinances, similar to those in Grants Pass, that are under York County Department of Parks and Recreation. The York County ordinance prohibits camping, and sleeping, in the Park System, which is defined as “any lands or facilities owned or leased by the County and designated or used by the County for park or recreational purposes” (pg 5).13 Violations within any part of the ordinance are punishable by a fine and/or jail time. Unlike Grants Pass, there are seemingly no ordinances for camping or sleeping on public property, aside from parks, in York County. Similarly, York City does not have an ordinance about public-camping or sleeping outside as of July 2024.

Despite York City’s current lack of local public camping ordinances, Shearer predicts that the unhoused population in York City will likely be affected by this ruling. Shearer shared that while no written ordinances are present in York City, it is known that the unhoused population will be impacted due to the amount of private property and citizens’ complaints of encampments. Shearer, who provides street outreach, stated that tensions were heightened between the community and the unhoused population. Similarly, there are concerns that other jurisdictions in York County will cause individuals experiencing homelessness to flee to York City, which will increase the tension and strain on the services provided by local shelters and nonprofits.1

Despite setbacks that the Supreme Court ruling will likely have on policies and programs supporting the unhoused populations, Kelly Blechertas, Program Coordinator for the York County Coalition on Homelessness, offered insight into two potential legal avenues to protect individuals experiencing homelessness from criminalization. Blechertas discussed how the Supreme Court ruled that the Eighth Amendment cannot be used to prevent public-camping ordinances to be enforced; however, this does not mean that other amendments or clauses cannot be used to protect the rights and welfare of individuals experiencing homelessness. According to Blechertas, some legal experts are contemplating the use of the Dormant Commerce Clause, which could punish states for causing individuals to flee to other states to escape strict ordinances. Additionally, those who are tried for violating public-camping ordinances could potentially use the necessity defense—their argument would be that an individual experiencing homelessness has no other choice but to sleep outside thus violating the ordinance.1

Explore Further

If you want to learn more about York’s unhoused population and how to get involved, view York County Coalition on Homelessness for more information. Additionally, you can view Friends and Neighbors of Pennsylvania’s FAQ and Events page. If you or someone you know is experiencing homelessness, consider using PA 211 to access local resources by dialing 211 or texting your zip code to 898-211.9

Kristie Houck is the Urban Collaborative Scholar-in-Residence at York College of Pennsylvania (YCP). During her time at YCP, Kristie has focused on housing research in York City. She is expected to graduate in May 2025 with a Masters of Public Policy and Administration (MPPA). Previously, Kristie’s professional experience was working with at-risk youth and their families involved in Children and Youth Services. Kristie can be found on Linkedin.

References

1 | K. Blechertas & R. Shearer, personal communication/interview, July 2024

2 | Butler, L. & Taylor, E.. (2022). A second chance: The impact of unsuccessful reentry and the need for reintegration resources in communities. The Community Dispatch. 15(4). https://cops.usdoj.gov/html/

3 | City of Grants Pass v. Johnson. 23-175 (U.S. 28 June 2024)

4 | Colburn, G. & Aldren, C.P. (2022). Homelessness is a housing problem: How structural factors explain U.S. patterns. University of California Press.

5 | Haines, J. (2024). States with the largest homeless populations. U.S. News. https://www.usnews.com/news/

6 | Friends and Neighbors of Pennsylvania, Inc. (n.d.). Leverage strengths. Create change. https://fnofpa.org/

7 | Jacobs, L. A., & Gottlieb, A. (2020). The effect of housing circumstances on recidivism: Evidence from a sample of people on probation in San Francisco. Criminal justice and behavior, 47(9), 1097-1115. 10.1177/0093854820942285

8 | National Low Income Housing Coalition. (2024). Out of reach: The high cost of housing. https://nlihc.org/oor

9 | Pennsylvania 211. (n.d.). Pennsylvania 211: Get connected. Get help.. https://www.pa211.org/211-

10 | United States Census. (2023). QuickFacts. https://www.census.gov/

11 | York County Coalition on Homelessness. (n.d.). About the coalition. https://yorkcountycoh.org/#:~:

12 | York County Economic Alliance. (2023). York County housing needs and conditions assessment. https://www.yorkcountyeap.org/

13 | YORK, PA., PARKS and REC. RULES and REG. ch. 75, § 1 (2020).